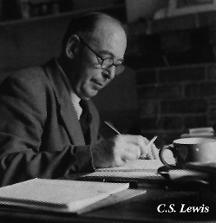

In the June/July issue of First Things Avery Cardinal Dulles presents a synopsis of C.S. Lewis' life and thought. For those not yet familiar with Lewis (and, believe it or not, there are a few), it makes a good introduction:

C.S. Lewis was a man of many parts. His novels, allegories, and children's books achieved enormous popularity. He excelled as a spiritual writer and had some standing as a poet. In the academic field he was competent in philosophy, a master of the Greek and Latin classics, and outstanding as a literary critic.

But he is best known today as an apologist, probably the most successful Christian apologist of the twentieth century. Forty and more years after his death, his influence remains unabated. His works are read by Protestants and Catholics with equal relish. Enough books have been written on Lewis to fill several shelves of a bookcase.

Dulles gives a fairly comprehensive overview of Lewis' work. He concludes by summarizing, from his own perspective, Lewis' relative strengths and weaknesses:

Lewis' eminent success as an apologist is due to several factors. A convert from atheism, he had experienced the difficulties from within and had discovered by experience what arguments could speak to unbelievers. He had a great gift for debating and wrote in a pleasing English style, free of heavy and technical language. He handled profound problems in simple words that could be understood by readers with no special training. Gifted with a lively imagination, he had an extraordinary facility for finding apt analogies from common life to illustrate abstract philosophical points. He was humble and unpretentious, willing to recognize the limits of his own knowledge. He concentrated on basic Christian beliefs and usually managed to avoid involvement in intra-Christian controversies.

The limits of Lewis are the flip side of his merits. Speaking to a broad and unsophisticated audience, he did not satisfy the scruples of soacademicianans, who found that he oversimplified complex problems. Avoiding technical terminology, he often failed to make distinctions that would be necessary to do justice to the subject matter. Having embraced no particular philosophical system other than a vague sort of Platonism, he frequently argued without the rigor expected in professional philosophical and theo logical circles.

As an apologist, moreover, Lewis tends to concentrate on the rational element in the approach to faith. But as he indicates in his own conversion story, it is not we alone who find the true faith. The God for whom we are searching has to find us, and we have to let Him do so. To speak too much as though faith were the result of a process of reasoning is a hazard built into apologetics. If Lewis had been willing to venture more deeply into theological waters, he might have spoken more extensively about the role of God in the process of conversion. Theologians in the great tradition show that divine grace influences even our initial perception of the evidences for Christianity. God'’s love, at work in our hearts, often enables us to synthesize data that might otherwise appear meaningless. It gives us what some theologians call the eyes of faith.For this reason the search for religious truth has to be accompanied by prayer.

As one might expect from a Catholic, Dulles' one lament is that Lewis, at least in his writings, appeared to hold a rather low view of church life and the sacraments. But Catholics probably think this is true of Protestants in general.

I believe C.S. Lewis is essential reading for any serious Christian. He had his flaws to be sure - all Christians do, and 2 Corinthians 4 teaches us that this is so that all men clearly see that it is God who is powerful, not man. The wonderful thing about Lewis is the extent to which his faith in Christ reached into every area of his life. He took seriously the command to "work out your faith."

He wanted to teach us to be philosophically consistent. And he did it all in a wonderfully warm and winsome way. Try to read the last few chapters of The Last Battle without weeping at the picture Lewis paints of the Christian's eternal destiny.